Not the end of the issue, unfortunately. Google isn’t the only search engine out there, which means that information may still appear in the results of other search engines. Other search engines are said to be developing similar processes in order to comply with the court’s interpretation, so that may help. Ultimately, however, even if all commercial search engines adopt this protocol, there are still other sites that are themselves searchable.

Searching within an individual site

This matters because having a link removed from search results doesn’t get rid of the information, it just makes it harder to find. No denying that this is helpful -- a court decision or news article from a decade ago is difficult to discover unless you know what you’re looking for, and without a helpful central search overview such things will be more likely to remain buried in the past. Some partial return to the days of privacy through obscurity one might say.

The Google decision was based on the precept that the actions of a search engine in constantly trawling the web meant that it did indeed collect, retrieve, records, organizes, discloses and stores information and accordingly does fall into the category of data control. When an individual site allows users to search the content on the site, this same categorization does not apply. Accordingly, individual sites will not be subject to the obligation (when warranted) to remove information from search results on request.

If we take it as written that everything on the Internet is ultimately about either sex or money (and of course cats), then the big question is, of course, how this can be commodified? And some sites have already figured that out.

Here’s What We Can Offer You

Enter Globe 24h, a self-described global database of public records: case law, notices and clinical trials. According to the site, this data is collected and made available because:

[w]e believe information should be free and open. Our goal is to make law accessible for free on the Internet. Our website provides access to court judgements, tribunal decisions, statutes and regulations from many jurisdictions. The information we provide access to is public and we believe everyone should have a right to access it, easily and without having to hire a lawyer. The public has a legitimate interest in this information — for example, information about financial scams, professional malpractice, criminal convictions, or public conduct of government officials. We do not charge for this service so we pay for the operating costs of the website with advertising.

A laudable goal, right?

The public records that are held by and searchable on the site contain personal information, and the site is careful to explain to users what rights they have over their information and how to exercise them. Most notably, the site offers clear and detailed explanation of how a user may request that their personal information be removed from the records – mailing a letter that includes personal information, pinpoint location of the document(s) at issue, documentary proof of identity, a signature card, an explanation of what information is requested to be removed and why. This letter is sent to a designated address (and will be returned if any component of the requirements is not met) and after a processing time of up to 15 days. Such a request, it is noted, may also involve forwarding of the letter and its personal information to data protection authorities.

But Wait, There’s More!!

Despite their claims that they bear the operating costs themselves (the implication being that they do so out of their deep commitment to access to information) the site does have a revenue stream.

Yes, for the low low price of €19 per document, the site will waive all these formalities and get your information off those documents (and out of commercial search engine caches as well) within 48 hours. Without providing a name, address, phone number, signature, or identification document. No need to be authenticated, no embarrassing explanation of why you want the information gone, no risk of being reported to State authorities, the ease of using email and no risk of having your request ignored or fail to be acted upon. It’s even done through PayPal, so it can theoretically be done completely anonymously.

If the only way to get this information removed were to pay the fee, the site would fall foul of data protection laws, but that’s not the case here. You don’t have to pay the money. That said, the options are set up so that one choice seems FAR preferable to the other….and it just happens to be the one from which the site profits.

There you have it – the commodification of the desire to be forgotten. Expect to see more approaches like this one.

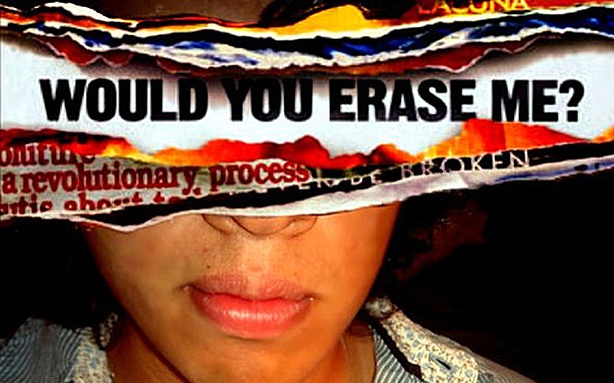

My takeaway? It’s not really possible to effectively manage what information is or isn’t available. Removing information entirely, removing it from search engine results, redacting it from documents or annotating it in hopes of mitigating its effect – in the long run information is out there and, if it is accurate, is likely going to be found and become incorporated into a data picture/reputation of a given individual.