Removing Unlawful Content Isn’t a Right to be Forgotten – It’s Justice

/A federal court decision released 30 January 2017 has (re)ignited discussion of the “right to be forgotten” (RTBF) in Canada.

The case revolved around the behaviour of Globe24h.com (the URL does not appear to be currently available, but it is noteworthy that their Facebook page is still online), a website that republishes Canadian court and tribunal decisions.

The publication of these decisions is not, itself, inherently problematic. Indeed, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) has previously found that an organization (unnamed in the finding, but presumably CanLii or a similar site) had collected, used and disclosed court decisions for appropriate purposes pursuant to subsection 5(3) of PIPEDA. The Commissioner determined that the company's purpose in republishing was to support the open courts principle, by making court and tribunal decisions more readily available to Canadian legal professionals and academics. Further, that the company's subscription-based research tools and services did not undermine the balance between privacy and the open courts principle that had been struck by Canadian courts, nor was the operation of those tools inconsistent with OPC’s guidance on the issue. It is important to note that this finding relied heavily on the decision by the organization NOT to allow search engines to index decisions within its database or otherwise making them available to non-subscribers.

In its finding, the OPC references another website – Globe24h.com – about which they had received multiple well-founded complaints. Regarding Globe24h.com, which did allow search engines to index decisions as well as hosting commercial advertising and charging a fee for removal of personal information, the Commissioner found that:

- He did have jurisdiction over the (Romanian-based) site, given its real and substantial connection to Canada;

- the site was not collecting, using and disclosing the information for exclusively journalistic purposes and thus was not exempt from PIPEDA’s requirements.

- that Globe24h’s purpose of making available Canadian court and tribunal decisions through search engines – which allows the sensitive personal information of individuals to be found by happenstance or by anyone, anytime for any purpose – was NOT one that a reasonable person would consider to be appropriate in the circumstances; and

- that although the information was publicly available, the site’s use was not consistent with the open courts principle for which it was originally made available, and thus PIPEDA’s requirement for knowledge and consent did apply to Globe24h.com.

Accordingly, he found the complaints well-founded.

From there, the complaint proceeded to Federal Court, with the Privacy Commissioner appearing as a party to the application.

The Federal Court concurred with the Privacy Commissioner that: PIPEDA did apply to Globe24h.com; that the site was engaged in commercial activity; and that it’s purposes were not exclusively journalistic. On reviewing its collection, use and disclosure of the information, the Court determined that the exclusion for publicly available information did not apply, and that Globe24h had contravened PIPEDA.

Where it gets interesting is in the remedies granted by the Court. Strongly influenced by the Privacy Commissioner’s submission, the Court:

- issued an order requiring Globe24h.com to correct its practices to comply with sections 5 to 10 of PIPEDA;

- relied upon s.16 of PIPEDA, which authorizes the Court grant remedies to address systemic non-compliance to issue a declaration that Gobe24h.com had contravened PIPEDA; and

- awarded damages in the amount of $5000 and costs in the amount of $300.

The reason this is interesting is the explicit recognition by the Court that:

A declaration that the respondent has contravened PIPEDA, combined with a corrective order, would allow the applicant and other complainants to submit a request to Google or other search engines to remove links to decisions on Globe24h.com from their search results. Google is the principal search engine involved and its policy allows users to submit this request where a court has declared the content of the website to be unlawful. Notably, Google’s policy on legal notices states that completing and submitting the Google form online does not guarantee that any action will be taken on the request. Nonetheless, it remains an avenue open to the applicant and others similarly affected. The OPCC contends that this may be the most practical and effective way of mitigating the harm caused to individuals since the respondent is located in Romania with no known assets. [para 88]

It is this line of argument that has fed response to the decision. The argument is that, by explicitly linking its declaration and corrective order with the ability of claimants to request that search engine’s remove the content at issue from their results, the decision has created a de facto RTBF in Canada.

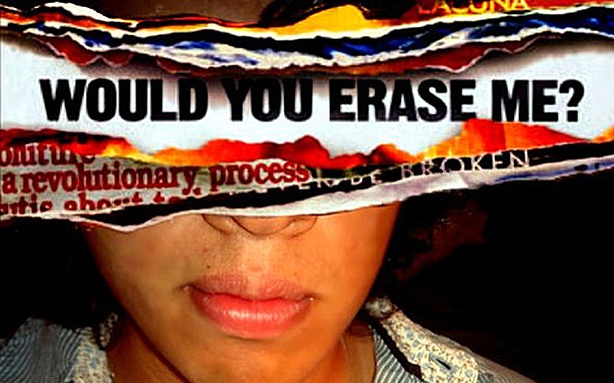

With all due respect, I disagree. A policy on removing content that a court has declared to be unlawful is not equivalent to a “right to be forgotten.” RTBF, as originally set out, recognized that under certain conditions (i.e., where specific information is inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant or excessive), individuals have the right to ask search engines to remove links to personal information about them. In contrast, the issue here is not that the information is “inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant or excessive” – rather, it is that the information has been declared UNLAWFUL.

The RTBF provision of the General Data Protection Regulation – Article 17 – sets out circumstances in which a request for erasure would not be honoured because there are principles at issue that transcend RTBF and justify keeping the data online – legal requirements, freedom of expression, interests of public health, and the necessity of processing the data for historical, statistical and scientific purposes.

We are not talking here about an overarching right to control dissemination of these publicly available court records. The importance of the open court principle was explicitly addressed by both the OPC and the Federal Court, and weighted in making their determinations. In so doing, the appropriate principled flexibility has been exercised – the very principled flexibility that is implicit in Article 17.

I do not dispute that a policy conversation about RTBF needs to take place, nor that explicitly setting out parameters and principles would be of assistance going forward. Perhaps the pending Supreme Court of Canada decision in Google v Equustek Solutions will provide that guidance.

Regardless, the decision in Globe24h.com does not create RTBF– rather, it exercises its power under PIPEDA to craft appropriate remedies to facilitate justice.